StudiO Studies: Ducks vs decorated sheds

StudiO Studies is an occasional series highlighting interesting, important and relevant moments from the history of architecture and design. These posts cover everything from theories and concepts to buildings and spaces – and of course, designers.

In their 1972 book, Learning from Las Vegas, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and their co-author Steven Izenour challenged the dominance of Modernism and proposed a new path for architects.

Based on their study of the Las Vegas Strip, they argued that, rather than relying solely on abstract forms, architecture should embrace symbolism and function. Their work became a cornerstone of Postmodernism and remains a touchstone for architectural theory.

Venturi and Scott Brown’s decision to study Las Vegas – a city characterised by neon signs, garish casinos, and commercial architecture – was revolutionary. At a time when architecture was dominated by Modernist ideals of purity and abstraction, the glitzy, populist aesthetics of Las Vegas seemed beneath serious inquiry. But the authors saw in it a rich language of signs and symbols that reflected cultural values and human behaviours.

In response, they developed the taxonomy of ‘ducks’ and ‘decorated sheds’ to critique Modernism and propose an alternative approach to design.

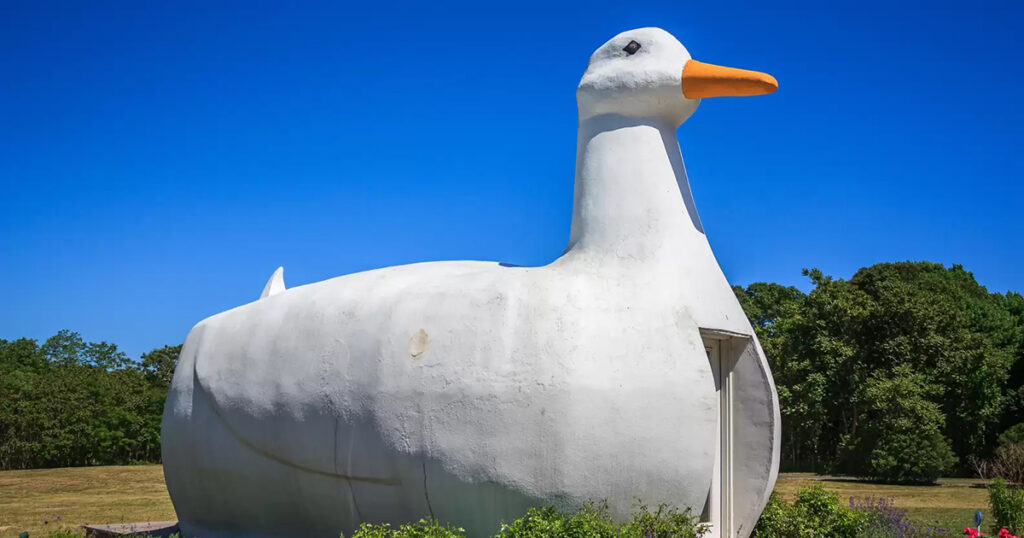

A ‘duck’ (named after the Big Duck, a duck-shaped farm shop selling poultry products in Long Island, NY) is a building in which form dominates function – “the architectural systems of space, structure, and program are submerged and distorted by an overall symbolic form.”

In their view, much of Modernist architecture embraced this philosophy, with entire buildings reduced to monumental, abstract statements. They criticised this approach for distorting practical considerations and turning buildings into oversized ornaments. (The Longaberger Big Basket building, completed in Ohio in 1997, is a striking later example of everything the authors of Learning from Las Vegas opposed.)

The ‘decorated shed’ meanwhile prioritises functionality, with meaning conveyed through applied decoration or signage. This is architecture in which “systems of space and structure are directly at the service of program, and ornament is applied independently.”

Historically, most architecture followed this approach, from medieval shopfronts to Classical temples, where applied decoration and symbolism communicated purpose and cultural meaning. Venturi and Scott Brown argued that Modernism’s rejection of ornament left buildings mute and soulless, particularly in institutional or corporate settings.

The principles outlined in Learning from Las Vegas are detectable in Venturi’s earlier Vanna Venturi House, built for his mother in 1964. With this design, he rejected the austerity of Modernism, using playful ornamentation and historical references.

The house’s oversized gable, centrally placed chimney, and symbolic façade expressed a return to architectural tradition while remaining functional and intimate. Like the Guild House (1963), which featured a golden television antenna symbolising its elderly residents’ favourite pastime and became an icon of Postmodernist architecture, the Vanna Venturi House exemplified the authors’ belief in meaningful, accessible design.

Challenging the prevailing heroism of Modernism and advocating for architecture that spoke to ordinary people, Learning from Las Vegas sparked fierce debate. By the late 20th century, the ‘decorated shed’ approach had influenced the rise of Postmodernism, with its eclectic styles, historical references and whimsical forms. Even Las Vegas itself evolved, with its Strip transforming into a display of exaggerated postmodern extravagance.

Of course, Postmodernism eventually gave way to new architectural trends, but the debate between ducks and decorated sheds goes on. Venturi and Scott Brown’s call to balance form, function, and meaning remains relevant, underscoring the timeless need for architecture to engage with human experience and cultural context – a responsibility that we relish at StudiO.