StudiO Studies: Architectural Cinema

StudiO Studies is an occasional series highlighting interesting, important and relevant moments from the history of architecture and design. These posts cover everything from theories and concepts to buildings and spaces – and of course, designers.

From arthouse indies to sci-fi blockbusters, plenty of films feature architects and architecture. But how many of them are worth watching?

Here are five of our favourites. Even when they fail at the cinematic level (and a couple definitely do), these movies all shed fascinating light on the world of design and the people who devote their lives to it.

The Fountainhead (1949)

Adapted by Ayn Rand from her controversial novel of the same name, this King Vidor-directed film stars Gary Cooper as the driven, individualistic architect Howard Roark.

Roark’s work and career is inspired by, and partly based on, that of Frank Lloyd Wright, who declined to be involved in the production, with the result that the architecture in the film ended up being “embarrassingly bad”, according to Rand. Supposedly brilliant, Roark does the reputation of architects no favours with his uncompromising, individualistic and occasionally criminal approach.

The Fountainhead broke even at the box office but was initially panned. The Hollywood Reporter claimed that “its characters are downright weird”, while Variety called the film “cold, unemotional, loquacious [and] completely devoted to hammering home the theme that man’s personal integrity stands above all law”. It was also called “shoddy, bombastic nonsense” (Cue), “the most asinine and inept movie that has come out of Hollywood in years” (The New Yorker) and “openly fascist” (The Daily Worker).

More recently, the film’s reputation has recovered somewhat. Revisiting it in 2011, critic Emanuel Levy described it as a “highly enjoyable, juicy Freudian melodrama”. Even Marxist philosopher Slavoj Žižek ranks it among his favourites: “ultracapitalist propaganda, but it’s so ridiculous that I cannot but love it.”

Strangers When We Meet (1960)

Though Kirk Douglas’s character Larry Coe is a Los Angeles architect in this somewhat soapy movie, his work is less central to the plot than his affair with neighbour Maggie, played by Kim Novak.

When Larry is commissioned by author Roger Altar to build an experimental house in Bel Air, it is Maggie’s encouragement to embrace his more unconventional instincts that prompts Larry to instigate the affair.

Though their extramarital escapades provide the bulk of the drama, the design and construction of Altar’s house is an important subplot. Art director Ross Bellah, with architect Carl Anderson, designed a real, 3,800-square-foot house, aligning the filming and construction schedules so that key scenes could be filmed at key stages of the build. The house still stands today at 930 Chantilly Road.

Time called the film “pure tripe”, while Variety acknowledged that despite being “a rather pointless, slow-moving story,” Strangers When We Meet is executed “with such skill that it charms the spectator into an attitude of relaxed enjoyment, much the same effect as that produced by a casual daydream fantasy.”

Columbus (2017)

When renowned architecture scholar Jae Yong Lee falls ill while delivering a lecture in Columbus, Indiana, his son Jin must travel from South Korea to be at his bedside. While in town, Jin befriends a local library assistant. This is Casey, a young woman who dreams of becoming an architect while caring for her mother, a recovering addict.

As this tender friendship develops, with important consequences for both, Casey and Jin explore the city of Columbus, which boasts an extraordinary wealth of Modernist architecture. Among the famous buildings that feature in this exquisitely beautiful film are the First Christian Church by Eliel Saarinen, the Irwin Union Bank, Miller House, and North Christian Church by Eliel’s son Eero Saarinen, and the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library by I. M. Pei.

In addition to being one of our favourites at StudiO, Columbus – director Kogonada’s debut – received rapturous reviews. “How do you make a ravishing romance about architecture?” asked Rolling Stone. “You’ll find the answer with Kogonada, whose debut feature is a spellbinder.” The Hollywood Reporter called it “quietly masterful”, while The New Yorker noted that “few films glow as brightly with the gem-like fire of precocious brilliance.”

Megalopolis (2024)

The antithesis of Columbus in every conceivable way, Francis Ford Coppola’s extravagant disaster has a viable claim to being one of the most spectacular disappointments in cinematic history. But it’s partly about an architect and admirably bonkers, so we’re including it here.

Adam Driver plays Cesar Catilina, a Nobel Prize-winning architect famed for inventing a revolutionary building material called Megalon. Haunted by the loss of his wife, whom he believes took her own life because of his obsession with his work, Catilina sets out to design and build a utopian urbanist community from which the film takes its title.

Though the film takes place in a speculative, science-fictional version of 21st-century America, the character of Catilina was inspired by various real-life figures. These include urban planner Robert Moses and architects Norman Bel Geddes, Walter Gropius, Raymond Loewy, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Brutalist (2024)

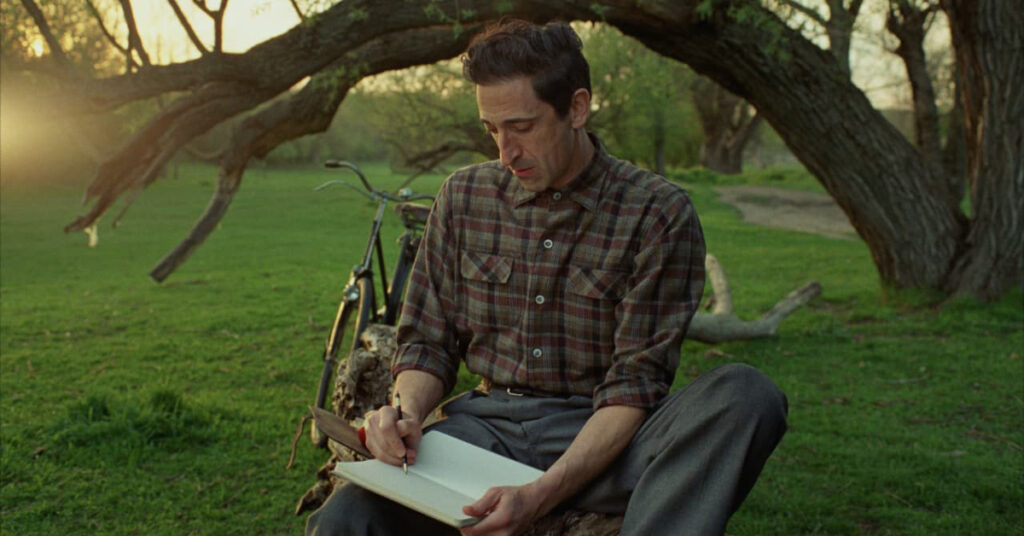

Adrien Brody won an Academy Award for his astonishing portrayal of László Tóth in this dark, audacious and powerful film. Tóth is a Bauhaus-trained architect from Hungary who immigrates to the USA after surviving the Holocaust, leaving behind his wife and orphaned niece.

As he struggles to assimilate and battles addiction, Tóth is commissioned by wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren to design The Van Buren Institute, a grand hilltop community center comprising a library, theatre, gymnasium and chapel. With the construction process growing increasingly fraught and his relationship with Van Buren becoming ever more toxic and abusive, it becomes clear that Tóth’s experiences at the hands of the Nazis are central to both his art and his mental state.

Though it would be hard to imagine a more dysfunctional or disturbing architect-client dynamic than the one depicted in Brady Corbet’s 3.5-hour epic, The Brutalist – which also picked up Oscars for its cinematography and score – is nonetheless a fascinating film for anyone interested in design. Ultimately more about trauma than architecture, it elucidates the integral connections between buildings, their designers and the historical conditions from which they emerge.