StudiO Studies: Psychogeography

StudiO Studies is an occasional series highlighting interesting, important and relevant moments from the history of architecture and design. These posts cover everything from theories and concepts to buildings and spaces – and of course, designers.

Developed by the Situationist International in the mid-20th century, psychogeography offers an interesting lens through which to explore and understand the built environment. It examines how urban spaces influence our emotions, behaviours and social interactions. Moving beyond maps and street plans, psychogeography highlights the invisible personal connections between people and places.

For urban designers and planners, psychogeography can offer a useful framework for rethinking how spaces are designed and experienced. Instead of viewing a city or town as a static arrangement of buildings and infrastructure, it encourages a more fluid, human-centred perspective – one that values the lived experience of the urban environment over its purely functional aspects.

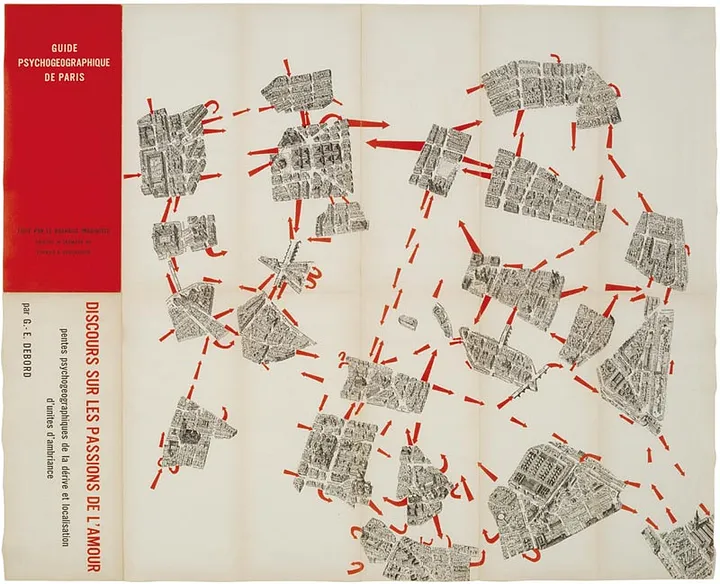

The most famous of the Situationists was probably Guy Debord. Debord defined psychogeography as the “study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.” In the six decades since it was published, Debord’s book The Society of the Spectacle – thought to have partly inspired the French revolts of May 1968 – has emerged as a classic work of sociology. (His claim that “all that was once directly lived has become mere representation” hits particularly hard in our age of Instagram and TikTok!)

One of the key practices of psychogeography is the dérive, or “drift”. The dérive is a method of wandering through a city with no fixed destination, allowing chance and the environment to shape the journey. Through the dérive, we can potentially uncover hidden narratives, forgotten histories, and unexpected emotional responses to urban landscapes. This practice is particularly relevant for contemporary architecture and urban planning, highlighting as it does the importance of pedestrian-scale design and the sensory impact of space.

In the UK, writers and artists have taken psychogeographic approaches when exploring the layered histories and psychological landscapes of cities like London. Figures such as Iain Sinclair, Peter Ackroyd and Will Self (who famously insisted on walking from the airport to St Peter Port when he appeared at the Guernsey Literary Festival) have used psychogeographic techniques to explore the mythologies and hidden tensions embedded within urban spaces. Their work underscores the fact that architecture is never just about physical structures – it’s also about the memories, stories and emotions attached to places by the people that inhabit or visit them.

For architects like us, channelling the spirit of the dérive helps make the design process more exciting and expansive. It helps us to consider how people might feel as they navigate a particular space. What emotions do different materials evoke? How do spatial arrangements encourage or discourage movement? How does the interplay of light, shadow, and sound contribute to an immersive sensory experience? Asking questions like these is essential for designing spaces that foster engagement, well-being and a sense of belonging.

With navigation tools like Google Maps increasingly dictating how we move through towns and cities, psychogeography reminds us of the value of spontaneous, unstructured engagement with urban space. As architects, it encourages us to design buildings and places that prioritise exploration, interaction, and discovery – spaces that invite people to slow down and look up.

Embracing the emotional and psychological dimensions of architecture and design enables us to create spaces that are not only functional but also rich with character and meaning.

From kitchens flooded with natural light (see La Fosse Cottage) to multi-layered public spaces packed with cultural references (see The Children’s Library), the principles of psychogeography are invaluable as we work to contribute to a more engaging and meaningful built environment.